“Make sure you don’t listen to LGBT people’s stories until you’ve established what the Bible says about it.” That was the counsel of a pastor friend of mine when he heard that our church was going to be discussing human sexuality in the church.

“Make sure you don’t listen to LGBT people’s stories until you’ve established what the Bible says about it.” That was the counsel of a pastor friend of mine when he heard that our church was going to be discussing human sexuality in the church.

We didn’t take that approach.

As our Study Team looked closely at Acts 15 in our sixth session, we realized how the early church handled disagreements about inclusion – and it was to listen to stories first. Of course, that doesn’t mean that the bible is not crucial – of course it is! It just means that all readings of the Bible are affected by our cultural context. As a friend of mine says, “There’s no view from nowhere” – meaning, there’s no way to read the Bible without bringing your own perspectives and experiences to it.

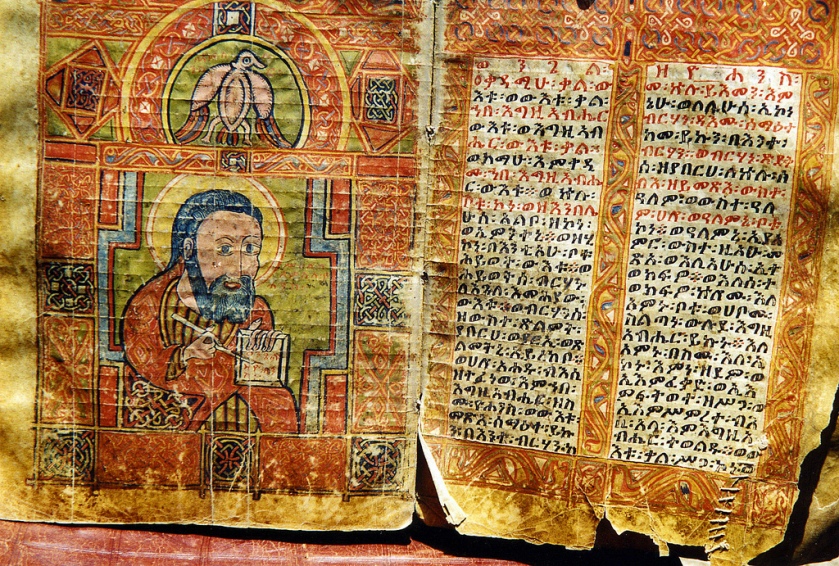

I realize that some of the folks reading this blog don’t claim to be Christians, so I’m guessing this conversation may seem esoteric. Just to catch you up to speed, from the Christian point of view, the Bible plays a critical role in how we understand God, people, history, morality, and culture.

As we think about the Bible, I want to ponder it in three ways not necessarily connected to each other: a graphic, a theological construct, and a parable. I find these to be helpful ways to get at the connection of the Bible and questions around LGBTQ persons in the church.

A Graphic: Three Types of Beliefs

I think people hold their different beliefs with differing degrees of conviction, depending on the belief. On this idea I found the Study Team readings from Greg Boyd* particularly helpful. In terms of Christian theology, I’d paraphrase Greg Boyd here by saying that there are core beliefs, important beliefs, and opinions.

I think of core beliefs as those foundational building blocks of the faith, around which there is general agreement across the church. There are not a lot of these. The way I think about these building blocks is that they are best summarized by the historic statement of the Christian faith, the Apostles’ Creed. That statement focuses mostly on Jesus, but includes the Trinity, that God made the world, the unity of all believers, the forgiveness of sins, and everlasting life. Notably, it doesn’t include how God made the world, or exactly how Jesus is both God and human, or how salvation works, or anything about Hell. It’s not that those are unimportant. They just are not core beliefs.

Important beliefs, the middle category, might include all sorts of things like views on women’s ordination, baptism, and end times. Opinions, the last category, are less weighty matters, like what kind of music to have in worship or what qualifications to have for a youth pastor.

If core beliefs are indeed limited to the Apostles’ Creed or some other summary of the Christian faith (like many churches post on their websites), then it’s inherent to this whole conversation that there can be differences around important beliefs like the morality of various sexual practices. Those important beliefs about sexual morality, gender identity, and leadership qualifications are, well, important. But it’s hard to imagine that they are core beliefs. If we’re willing to admit that, wouldn’t it be realistic and helpful and even edifying to embrace people with differing views around these important beliefs… including beliefs about LGBTQ people in the church?

A Theological Construct: Is The Bible Inerrant?

The second perspective on how the Bible informs what we think about LGBTQ issues has to do with the weighty theological construct known as inerrancy. Holding to inerrancy, or not, makes a big difference in how you think about the topics at hand.

In our tenth session together, the Study Team considered The Chicago Statement on Inerrancy and The Chicago Statement on Biblical Hermeneutics as well as numerous other articles and books about how to understand the Bible (see Session 10 in our Syllabus). Browse through them briefly, and you’ll get a sense for them. The Chicago statements tend towards being very clear about how clear the Bible is. One of the affirmations that stood out to me during our Study Team session was Article VII from the second statement:

We affirm that the meaning expressed in each biblical text is single, definite and fixed.

After the diligent work we’d done on Genesis 1 & 2 and on the best traditional and progressive arguments on Romans 1, I really struggled with the simplicity of the Chicago Statement. Frankly, it seemed oversimplified. It’s not that the biblical texts don’t have meaning, it’s just that it’s so darn hard to figure out what that meaning is, particularly as a single text is weighed with all the other texts, each with their own emphases. But this isn’t an issue with just LGBTQ issues. Sociologist Christian Smith summarizes the breadth of the tensions Christians face on various issues:

The disagreements, to be specific, are over inerrancy (inerrantism versus infallibalist), providence (Calvinist versus Arminian), divine foreknowledge (Arminian versus Calvinist versus Open views), Genesis (the young earth, day-age, restoration, and literal views), divine image in humanity (the substantival, functional, and relational views), Christology (classical versus kenotic), atonement (penal substitution, Christus Victor, and moral government views), salvation (TULIP versus Arminian), sanctification (Lutheran, Reformed, Keswick, and Wesleyan), eternal security (eternal versus conditional), the destiny of the unevangelized (the restrictive, universal opportunity, postmortem evangelism, and inclusive views), baptism (believer’s versus infant baptism), the Lord’s Supper (spiritual presence versus memorial), charismatic gifts (continuationism versus cessationism), women in ministry (complementarian versus egalitarian), the millennium (premillennialism, postmillennialism, amillennialism), and hell (the classical view versus annihilationism).

…On important matters the Bible apparently is not clear, consistent, and univocal enough to enable the best-intentioned, most highly skilled, believing readers to come to agreement as to what it teaches. That is an empirical, historical, undeniable, and ever-present reality.

Even very conservative scholars like D.A. Carson* recognize this wide spectrum of beliefs amongst those who hold a high view of scripture. So I struggle with how inerrancy is defined by the Chicago Statements and how it plays out in churches because it assumes a degree of certainty about what it calls the “literal, or normal, sense” of scriptures that I (and I believe most others) don’t see there.

Personally, I’m far more comfortable with how the Bible describes itself in 2 Timothy 3:16, which is that it’s inspired by God and it’s true: “All Scripture is God-breathed and is useful for teaching, rebuking, correcting, and training in righteousness.” It seems that God was content to give us a Bible that doesn’t make itself starkly clear on all points, and yet is still inspired. I think that’s exactly the Bible God meant for us to have!

Practically speaking, this means that when we look at the Bible, there can be room for different perspectives on the same events and their meaning. Why else would there be four different Gospel accounts, after all? Or why include two different histories of the same kings in Israel’s history, each with very different emphases? Or why would Hebrews and Romans look at predestination so differently?

From my experience, which is limited for sure, inerrancy is more of a mindset about certainty than it is a theology. That longing for certainty prioritizes clarity, which leads to neatness and cleanness in the realm of theology. That tidy theology then tends to domineer the experiences and perspectives of sexual minorities, often attempting to smother differing ways to think about the Bible passages dealing with sexuality and gender.

I know people who are not inerrantists who fall on all sides of the spectrum of belief about LGBTQ issues, including both traditionalist and progressive. What encourages me about these people is their openness to dialogue, their curiosity, and their willingness to wrestle with the bible’s variety and nuance. I find this perspective a lot healthier in many areas, including conversations around sexuality and the Bible.

A Parable: Three Umpires

About twenty years ago, when I was trying to figure out how to think about postmodernism, I came across a parable that made a lot of sense to me. Now it helps me think about how the Bible speaks to questions surrounding inclusion of LGBTQ people in the church. It goes like this:

Three baseball umpires are sitting at a bar talking about the game. ‘There’s balls and there’s strikes,’ says the first, ‘and I call ‘em the way they are.’

The second umpire protests, “There’s balls and there’s strikes. I call ‘em and that’s the way they are.”

The third umpire thinks for a minute and then speaks up. “There’s balls and there’s strikes, and I call ‘em the way I see ‘em.”

Modernists approach truth as if it is easily and directly discernible; they believe they have direct access to meaning, therefore they say “I call ‘em the way they are.” The postmodernists leave everything up to the subject, with no connection to a separate reality that’s out there, so they say “I call ‘em and that’s the way they are.” Then there are what might be called the Critical Realists, those who recognize that there is indeed a reality out there which we’re trying to understand, but we don’t see it perfectly (it’s as though now we see through a mirror, dimly). The Critical Realists realize that because of their own perspective and experiences, they can only do their best to get at that reality. Thus, they say “I call ‘em the way I see ‘em.”

I’ve grown tired of the easy answers on both sides, whether it’s throwing down a clobber verse out of context or a pronouncement like “whatever you feel is right is right.” The clobber-er sounds like the first umpire to me, and the feel-er sounds like the second; one lays claim to the one true interpretation, and the other implies there’s no absolutes out there besides their own experience. I suppose they are similar in that they each try to define reality exclusively.

As I engage with more and more people around the Bible and LGBTQ concerns, I’ve become increasingly convinced that the best I can do is to say with the third umpire, “I call ‘em the way I see ‘em.” I’m doing my best, and it’s not easy, not neat, and not clean. And as best as I can tell that’s actually how the early church handled tricky questions about inclusion of the Gentiles, evidenced by the fact that their solution was short-lived and reversed a couple of times (see Mark 7, Acts 15, 1 Corinthians 8, 10, Romans 14-15, Revelation 2).

When it comes to sexuality and gender issues in the church, it’s not just the Bible that we’re talking about, although it is that. It’s how we view the Bible.

*D. A. Carson notes that “I speak to those with a high view of Scripture: it is very distressing to contemplate how many differences there are among us as to what Scripture actually says… The fact remains that among those who believe the canonical sixty-six books are nothing less than the Word of God written there is a disturbing array of mutually incompatible theological opinions.”

*Greg Boyd, Benefit of The Doubt. Chapter 8 – A Solid Center. Chapter 9 – The Center of Scripture.

I appreciate the honesty about the difficulties in interpreting the Bible. In my experience, the hard next steps are determining (a) what falls into each degree of conviction and (b) how to accept ambiguity in the Bible without treating the question as irrelevant. It’s very easy to say “Smart people have differing perspectives” as a way to avoid the hard questions.

LikeLike

As always I enjoyed reading this post. When talking about biblical inerrancy it amazes me how many different topics can fall within the three categories, [CIO (core, important, opinion)] but what seems interest me more these days are the explanations from people as to why certain topics fall into the various categories for them. As we all bare the unfortunate (or maybe fortune) burden of being flawed humans, we will not unanimously agree on all these classifications, so the real struggle of growing enough to learn how to exist harmoniously with others who differ from us so starkly persists. How do we hold our CIOs firm enough to guide our journeys, while at the same time holding them lose enough to make room from someone else whose CIOs differ from ours? How do we not judge the CIO of our neighbor AND find peace in communion with them? I’m still searching for these answers…

LikeLike

You nailed it. How to have things you actually hold to and not judge your neighbor’s beliefs… and yet still engage with them constructively to grow and learn yourself and to challenge and push them. May God have mercy on us all to do this well.

LikeLike

A continued thank you for your thoughts, insights and process. Love and Grace abound in you! Blessings.

LikeLike